Entheogens & Existential Intelligence:

The Use of “Plant Teachers” as Cognitive Tools

By Kenneth Tupper

From: www.ayahuasca.com

Download: Full Text Version

Painting by Yvonne McGillivray

Abstract

In light of recent specific liberalizations in drug laws in some countries, this article investigates the potential of entheogens (i.e. psychoactive plants used as spiritual sacraments) as tools to facilitate existential intelligence. “Plant teachers” from the Americas such as ayahuasca, psilocybin mushrooms, peyote, and the Indo-Aryan soma of Eurasia are examples of both past- and presently-used entheogens. These have all been revered as spiritual or cognitive tools to provide a richer cosmological understanding of the world for both human individuals and cultures. I use Howard Gardner’s (1999a) revised multiple intelligence theory and his postulation of an “existential” intelligence as a theoretical lens through which to account for the cognitive possibilities of entheogens and explore potential ramifications for education.

Introduction

In this article I assess and further develop the possibility of an “existential” intelligence as postulated by Howard Gardner (1999a). Moreover, I entertain the possibility that some kinds of psychoactive substances—entheogens—have the potential to facilitate this kind of intelligence. This issue arises from the recent liberalization of drug laws in several Western industrialized countries to allow for the sacramental use of ayahuasca, a psychoactive tea brewed from plants indigenous to the Amazon. I challenge readers to step outside a long-standing dominant paradigm in modern Western culture that a priori regards “hallucinogenic” drug use as necessarily maleficent and devoid of any merit. I intend for my discussion to confront assumptions about drugs that have unjustly perpetuated the disparagement and prohibition of some kinds of psychoactive substance use. More broadly, I intend for it to challenge assumptions about intelligence that constrain contemporary educational thought.

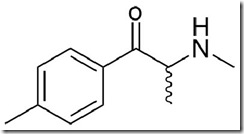

“Entheogen” is a word coined by scholars proposing to replace the term “psychedelic” (Ruck, Bigwood, Staples, Ott, & Wasson, 1979), which was felt to overly connote psychological and clinical paradigms and to be too socio-culturally loaded from its 1960s roots to appropriately designate the revered plants and substances used in traditional rituals. I use both terms in this article: “entheogen” when referring to a substance used as a spiritual or sacramental tool, and “psychedelic” when referring to one used for any number of purposes during or following the so-called psychedelic era of the 1960s (recognizing that some contemporary non-indigenous uses may be entheogenic—the categories are by no means clearly discreet). What kinds of plants or chemicals fall into the category of entheogen is a matter of debate, as a large number of inebriants—from coca and marijuana to alcohol and opium—have been venerated as gifts from the gods (or God) in different cultures at different times. For the purposes of this article, however, I focus on the class of drugs that Lewin (1924/1997) termed “phantastica,” a name deriving from the Greek word for the faculty of imagination (Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 1973). Later these substances became known as hallucinogens or psychedelics, a class whose members include lysergic acid derivatives, psilocybin, mescaline and dimethyltryptamine. With the exception of mescaline, these all share similar chemical structures; all, including mescaline, produce similar phenomenological effects; and, more importantly for the present discussion, all have a history of ritual use as psychospiritual medicines or, as I argue, cultural tools to facilitate cognition (Schultes & Hofmann, 1992).

The issue of entheogen use in modern Western culture becomes more significant in light of several legal precedents in countries such as Brazil, Holland, Spain and soon perhaps the United States and Canada. Ayahuasca, which I discuss in more detail in the following section on “plant teachers,” was legalized for religious use by non-indigenous people in Brazil in 1987i. One Brazilian group, the Santo Daime, was using its sacrament in ceremonies in the Netherlands when, in the autumn of 1999, authorities intervened and arrested its leaders. This was the first case of religious intolerance by a Dutch government in over three hundred years. A subsequent legal challenge, based on European Union religious freedom laws, saw them acquitted of all charges, setting a precedent for the rest of Europe (Adelaars, 2001). A similar case in Spain resulted in the Spanish government granting the right to use ayahuasca in that country. A recent court decision in the United States by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, September 4th, 2003, ruled in favour of religious freedom to use ayahuasca (Center for Cognitive Liberty and Ethics, 2003). And in Canada, an application to Health Canada and the Department of Justice for exemption to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act is pending, which may permit the Santo Daime Church the religious use of their sacrament, known as Daime or Santo Daimeii (J.W. Rochester, personal communication, October 8th, 2003)

One of the questions raised by this trend of liberalization in otherwise prohibitionist regulatory regimes is what benefits substances such as ayahuasca have. The discussion that follows takes up this question with respect to contemporary psychological theories about intelligence and touches on potential ramifications for education. The next section examines the metaphor of “plant teachers,” which is not uncommon among cultures that have traditionally practiced the entheogenic use of plants. Following that, I use Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences (1983) as a theoretical framework with which to account for cognitive implications of entheogen use. Finally, I take up a discussion of possible relevance of existential intelligence and entheogens to education.

Plant Teachers

Before moving on to a broader discussion of intelligence(s), I will provide some background on ayahuasca and entheogens. Ayahuasca has been a revered “plant teacher” among dozens of South American indigenous peoples for centuries, if not longer (Luna, 1984; Schultes & Hofmann, 1992). The word ayahuasca is from the Quechua language of indigenous peoples of Ecuador and Peru, and translates as “vine of the soul” (Metzner, 1999). Typically, it refers to a tea made from a jungle liana, Banisteriopsis caapi, with admixtures of other plants, but most commonly the leaves of a plant from the coffee family, Psychotria viridis (McKenna, 1999). These two plants respectively contain harmala alkaloids and dimethyltryptamine, two substances that when ingested orally create a biochemical synergy capable of producing profound alterations in consciousness (Grob, et al., 1996; McKenna, Towers & Abbot, 1984). Among the indigenous peoples of the Amazon, ayahuasca is one of the most valuable medicinal and sacramental plants in their pharmacopoeias. Although shamans in different tribes use the tea for various purposes, and have varying recipes for it, the application of ayahuasca as an effective tool to attain understanding and wisdom is one of the most prevalent (Brown, 1986; Dobkin de Rios, 1984).

Notwithstanding the explosion of popular interest in psychoactive drugs during the 1960s, ayahuasca until quite recently managed to remain relatively obscure in Western cultureiii. However, the late 20th century saw the growth of religious movements among non-indigenous people in Brazil syncretizing the use of ayahuasca with Christian symbolism, African spiritualism, and native ritual. Two of the more widespread ayahuasca churches are the Santo Daime (Santo Daime, 2004) and the União do Vegetal (União do Vegetal, 2004). These organizations have in the past few decades gained legitimacy as valid, indeed valuable, spiritual practices providing social, psychological and spiritual benefits (Grob, 1999; Riba, et al., 2001).

Ayahuasca is not the only “plant teacher” in the pantheon of entheogenic tools. Other indigenous peoples of the Americas have used psilocybin mushrooms for millennia for spiritual and healing purposes (Dobkin de Rios, 1973; Wasson, 1980). Similarly, the peyote cactus has a long history of use by Mexican indigenous groups (Fikes, 1996; Myerhoff, 1974; Stewart, 1987), and is currently widely used in the United States by the Native American Church (LaBarre, 1989; Smith & Snake, 1996). And even in the early history of Western culture, the ancient Indo-Aryan texts of the Rig Veda sing the praises of the deified Soma (Pande, 1984). Although the taxonomic identity of Soma is lost, it seems to have been a plant or mushroom and had the power to reliably induce mystical experiences—an “entheogen” par excellence (Eliade, 1978; Wasson, 1968). The variety of entheogens extends far beyond the limited examples I have offered here. However, ayahuasca, psilocybin mushrooms, peyote and Soma are exemplars of plants which have been culturally esteemed for their psychological and spiritual impacts on both individuals and communities.

In this article I argue that the importance of entheogens lies in their role as tools, as mediators between mind and environment. Defining a psychoactive drug as a tool—perhaps a novel concept for some—invokes its capacity to effect a purposeful change on the mind/body. Commenting on Vygotsky’s notions of psychological tools, John-Steiner and Souberman (1978) note that “tool use has . . . important effects upon internal and functional relationships within the human brain” (p. 133). Although they were likely not thinking of drugs as tools, the significance of this observation becomes even more literal when the tools in question are plants or chemicals ingested with the intent of affecting consciousness through the manipulation of brain chemistry. Indeed, psychoactive plants or chemicals seem to defy the traditional bifurcation between physical and psychological tools, as they affect the mind/body (understood by modern psychologists to be identical).

It is important to consider the degree to which the potential of entheogens comes not only from their immediate neuropsychological effects, but also from the social practices—rituals—into which their use has traditionally been incorporated (Dobkin de Rios, 1996; Smith, 2000). The protective value that ritual provides for entheogen use is evident from its universal application in traditional practices (Weil, 1972/1986). Medical evidence suggests that there are minimal physiological risks associated with psychedelic drugs (Callaway, et al., 1999; Grinspoon & Bakalar, 1979/1998; Julien, 1998). Albert Hofmann (1980), the chemist who first accidentally synthesized and ingested LSD, contends that the psychological risks associated with psychedelics in modern Western culture are a function of their recreational use in unsafe circumstances. A ritual context, however, offers psychospiritual safeguards that make the potential of entheogenic “plant teachers” to enhance cognition an intriguing possibility.

Existential Intelligence

Howard Gardner (1983) developed a theory of multiple intelligences that originally postulated seven types of intelligence (iv). Since then, he has added a “naturalist” intelligence and entertained the possibility of a “spiritual” intelligence (1999a; 1999b). Not wanting to delve too far into territory fraught with theological pitfalls, Gardner (1999a) settled on looking at “existential” intelligence rather than “spiritual” intelligence (p. 123). Existential intelligence, as Gardner characterizes it, involves having a heightened capacity to appreciate and attend to the cosmological enigmas that define the human condition, an exceptional awareness of the metaphysical, ontological and epistemological mysteries that have been a perennial concern for people of all cultures (1999a).

In his original formulation of the theory, Gardner challenges (narrow) mainstream definitions of intelligence with a broader one that sees intelligence as “the ability to solve problems or to fashion products that are valued in at least one culture or community” (1999a, p. 113). He lays out eight criteria, or “signs,” that he argues should be used to identify an intelligence; however, he notes that these do not constitute necessary conditions for determining an intelligence, merely desiderata that a candidate intelligence should meet (1983, p. 62). He also admits that none of his original seven intelligences fulfilled all the criteria, although they all met a majority of the eight. For existential intelligence, Gardner himself identifies six which it seems to meet; I will look at each of these and discuss their merits in relation to entheogens.

One criterion applicable to existential intelligence is the identification of a neural substrate to which the intelligence may correlate. Gardner (1999a) notes that recent neuropsychological evidence supports the hypothesis that the brain’s temporal lobe plays a key role in producing mystical states of consciousness and spiritual awareness (p. 124-5; LaPlante, 1993; Newberg, D’Aquili & Rause, 2001). He also recognizes that “certain brain centres and neural transmitters are mobilized in [altered consciousness] states, whether they are induced by the ingestion of substances or by a control of the will” (Gardner, 1999a, p.125). Another possibility, which Gardner does not explore, is that endogenous dimethyltryptamine (DMT) in humans may play a significant role in the production of spontaneous or induced altered states of consciousness (Pert, 2001). DMT is a powerful entheogenic substance that exists naturally in the mammalian brain (Barker, Monti & Christian, 1981), as well as being a common constituent of ayahuasca and the Amazonian snuff, yopo (Ott, 1994). Furthermore, DMT is a close analogue of the neurotransmitter 5-hydroxytryptamine, or serotonin. It has been known for decades that the primary neuropharmacological action of psychedelics has been on serotonin systems, and serotonin is now understood to be correlated with healthy modes of consciousness.

One psychiatric researcher has recently hypothesized that endogenous DMT stimulates the pineal gland to create such spontaneous psychedelic states as near-death experiences (Strassman, 2001). Whether this is correct or not, the role of DMT in the brain is an area of empirical research that deserves much more attention, especially insofar as it may contribute to an evidential foundation for existential intelligence.

Another criterion for an intelligence is the existence of individuals of exceptional ability within the domain of that intelligence. Unfortunately, existential precocity is not something sufficiently valued in modern Western culture to the degree that savants in this domain are commonly celebrated today. Gardner (1999a) observes that within Tibetan Buddhism, the choosing of lamas may involve the detection of a predisposition to existential intellect (if it is not identifying the reincarnation of a previous lama, as Tibetan Buddhists themselves believe) (p. 124). Gardner also cites Czikszentmilhalyi’s consideration of the “early-emerging concerns for cosmic issues of the sort reported in the childhoods of future religious leaders like Gandhi and of several future physicists” (Gardner, 1999a, p. 124; Czikszentmilhalyi, 1996). Presumably, some individuals who are enjoined to enter a monastery or nunnery at a young age may be so directed due to an appreciable manifestation of existential awareness. Likewise, individuals from indigenous cultures who take up shamanic practice—who “have abilities beyond others to dream, to imagine, to enter states of trance” (Larsen, 1976, p. 9)—often do so because of a significant interest in cosmological concerns at a young age, which could be construed as a prodigious capacity in the domain of existential intelligencev (Eliade, 1964; Greeley, 1974; Halifax, 1979).

The third criterion for determining an intelligence that Gardner suggests is an identifiable set of core operational abilities that manifest that intelligence. Gardner finds this relatively unproblematic and articulates the core operations for existential intelligence as:

the capacity to locate oneself with respect to the farthest reaches of the cosmos—the infinite no less than the infinitesimal—and the related capacity to locate oneself with respect to the most existential aspects of the human condition: the significance of life, the meaning of death, the ultimate fate of the physical and psychological worlds, such profound experiences as love of another human being or total immersion in a work of art. (1999a, p. 123)

Gardner notes that as with other more readily accepted types of intelligence, there is no specific truth that one would attain with existential intelligence—for example, as musical intelligence does not have to manifest itself in any specific genre or category of music, neither does existential intelligence privilege any one philosophical system or spiritual doctrine. As Gardner (1999a) puts it, “there exists [with existential intelligence] a species potential—or capacity—to engage in transcendental concerns that can be aroused and deployed under certain circumstances” (p. 123). Reports on uses of psychedelics by Westerners in the 1950s and early 1960s—generated prior to their prohibition and, some might say, profanation—reveal a recurrent theme of spontaneous mystical experiences that are consistent with enhanced capacity of existential intelligence (Huxley, 1954/1971; Masters & Houston, 1966; Pahnke, 1970; Smith, 1964; Watts, 1958/1969).

Another criterion for admitting an intelligence is identifying a developmental history and a set of expert “end-state” performances for it. Pertaining to existential intelligence, Gardner notes that all cultures have devised spiritual or metaphysical systems to deal with the inherent human capacity for existential issues, and further that these respective systems invariably have steps or levels of sophistication separating the novice from the adept. He uses the example of Pope John XXIII’s description of his training to advance up the ecclesiastic hierarchy as a contemporary illustration of this point (1999a, p. 124). However, the instruction of the neophyte is a manifest part of almost all spiritual training and, again, the demanding process of imparting of shamanic wisdom—often including how to effectively and appropriately use entheogens—is an excellent example of this process in indigenous cultures (Eliade, 1964).

A fifth criterion Gardner suggests for an intelligence is determining its evolutionary history and evolutionary plausibility. The self-reflexive question of when and why existential intelligence first arose in the Homo genus is one of the perennial existential questions of humankind. That it is an exclusively human trait is almost axiomatic, although a small but increasing number of researchers are willing to admit the possibility of higher forms of cognition in non-human animals (Masson & McCarthy, 1995; Vonk, 2003). Gardner (1999a) argues that only by the Upper Paleolithic period did “human beings within a culture possess a brain capable of considering the cosmological issues central to existential intelligence” (p. 124) and that the development of a capacity for existential thinking may be linked to “a conscious sense of finite space and irreversible time, two promising loci for stimulating imaginative explorations of transcendental spheres” (p. 124). He also suggests that “thoughts about existential issues may well have evolved as responses to necessarily occurring pain, perhaps as a way of reducing pain or better equipping individuals to cope with it” (Gardner, 1999a, p. 125). As with determining the evolutionary origin of language, tracing a phylogenesis of existential intelligence is conjectural at best. Its role in the development of the species is equally difficult to assess, although Winkelman (2000) argues that consciousness and shamanic practices—and presumably existential intelligence as well—stem from psychobiological adaptations integrating older and more recently evolved structures in the triune hominid brain. McKenna (1992) goes even so far as to postulate that the ingestion of psychoactive substances such as entheogenic mushrooms may have helped stimulate cognitive developments such as existential and linguistic thinking in our proto-human ancestors. Some researchers in the 1950s and 1960s found enhanced creativity and problem-solving skills among subjects given LSD and other psychedelic drugs (Harman, McKim, Mogar, Fadiman & Stolaroff, 1966; Izumi, 1970; Krippner, 1985; Stafford & Golightly, 1967), skills which certainly would have been evolutionarily advantageous to our hominid ancestors. Such avenues of investigation are beginning to be broached again by both academic scholars and amateur psychonauts (Dobkin de Rios & Janiger, 2003; Spitzer, et al., 1996; MAPS Bulletin, 2000).

The final criterion Gardner mentions as applicable to existential intelligence is susceptibility to encoding in a symbol system. Here, again, Gardner concedes that there is abundant evidence in favour of accepting existential thinking as an intelligence. In his words, “many of the most important and most enduring sets of symbol systems (e.g., those featured in the Catholic liturgy) represent crystallizations of key ideas and experiences that have evolved within [cultural] institutions” (1999a, p. 123). Another salient example that illustrates this point is the mytho-symbolism ascribed to ayahuasca visions among the Tukano, an Amazonian indigenous people. Reichel-Dolmatoff (1975) made a detailed study of these visions by asking a variety of informants to draw representations with sticks in the dirt (p. 174). He compiled twenty common motifs, observing that most of them bear a striking resemblance to phosphene patterns (i.e. visual phenomena perceived in the absence of external stimuli or by applying light pressure to the eyeball) compiled by Max Knoll (Oster, 1970). The Tukano interpret these universal human neuropsychological phenomena as symbolically significant according to their traditional ayahuasca-steeped mythology, reflecting the codification of existential ideas within their culture.

Narby (1998) also examines the codification of symbols generated during ayahuasca experiences by tracing similarities between intertwining snake motifs in the visions of Amazonian shamans and the double-helix structure of deoxyribonucleic acid. He found remarkable similarities between representations of biological knowledge by indigenous shamans and those of modern geneticists. More recently, Narby (2002) has followed up on this work by bringing molecular biologists to the Amazon to participate in ayahuasca ceremonies with experiences shamans, an endeavour he suggests may provide useful cross-fertilization in divergent realms of human knowledge.

The two other criteria of an intelligence are support from experimental psychological tasks and support from psychometric findings. Gardner suggests that existential intelligence is more debatable within these domains, citing personality inventories that attempt to measure religiosity or spirituality; he notes, “it remains unclear just what is being probed by such instruments and whether self-report is a reliable index of existential intelligence” (1999a, p. 125). It seems transcendental states of consciousness and the cognition they engender do not lend themselves to quantification or easy replication in psychology laboratories. However, Strassman, Qualls, Uhlenhuth, & Kellner (1994) developed a psychometric instrument—the Hallucinogen Rating Scale—to measure human responses to intravenous administration of DMT, and it has since been reliably used for other psychedelic experiences (Riba, Rodriguez-Fornells, Strassman, & Barbanoj, 2001).

One historical area of empirical psychological research that did ostensibly stimulate a form of what might be considered existential intelligence was clinical investigations into psychedelics. Until such research became academically unfashionable and then politically impossible in the early 1970s, psychologists and clinical researchers actively explored experimentally-induced transcendent experiences using drugs in the interests of both pure science and applied medical treatments (Abramson, 1967; Cohen, 1964; Grinspoon & Bakalar, 1979/1998; Masters & Houston, 1966). One of the more famous of these was Pahnke’s (1970) so-called “Good Friday” experiment, which attempted to induce spiritual experiences with psilocybin within a randomized double-blind control methodology. His conclusion that mystical experiences were indeed reliably produced, despite methodological problems with the study design, was borne out by a critical long-term follow-up (Doblin, 1991), which raises intriguing questions about both entheogens and existential intelligence.

Studies such as Pahnke’s (1970), despite their promise, were prematurely terminated due to public pressure from a populace alarmed by burgeoning contemporary recreational drug use. Only about a decade ago did the United States government give researchers permission to renew (on a very small scale) investigations into psychedelics (Strassman 2001; Strassman & Qualls, 1994). Cognitive psychologists are also taking an interest in entheogens such as ayahuasca (Shanon, 2002). Regardless of whether support for existential intelligence can be established psychometrically or in experimental psychological tasks, Gardner’s theory expressly stipulates that not all eight criteria must be uniformly met in order for an intelligence to qualify. Nevertheless, Gardner claims to “find the phenomenon perplexing enough, and the distance from other intelligences great enough” (1999a, p. 127) to be reluctant “at present to add existential intelligence to the list . . . . At most [he is] willing, Fellini-style, to joke about ‘8½ intelligences’” (p. 127). I contend that research into entheogens and other means of altering consciousness will further support the case for treating existential intelligence as a valid cognitive domain.

Educational Implications?

By recapitulating and augmenting Gardner’s discussion of existential intelligence, I hope to have strengthened the case for its inclusion as a valid cognitive domain. However, doing so raises questions of what ramifications an acceptance of existential intelligence would have for contemporary Western educational theory and practice. How might we foster this hitherto neglected intelligence and allow it to be used in constructive ways? There is likely a range of educational practices that could be used to stimulate cognition in this domain, many of which could be readily implemented without much controversy.vi Yet I intentionally raise the prospect of using entheogens in this capacity—not with young children, but perhaps with older teens in the passage to adulthood—to challenge theorists, policy-makers and practitioners.vii

The potential of entheogens as tools for education in contemporary Western culture was identified by Aldous Huxley. Although better known as a novelist than as a philosopher of education, Huxley spent a considerable amount of time—particularly as he neared the end of his life—addressing the topic of education. Like much of his literature, Huxley’s observations and critiques of the socio-cultural forces at work in his time were cannily prescient; they bear as much, if not more, relevance in the 21st century as when they were written. Most remarkably, and relevant to my thesis, Huxley saw entheogens as possible educational tools:

Under the current dispensation the vast majority of individuals lose, in the course of education, all the openness to inspiration, all the capacity to be aware of other things than those enumerated in the Sears-Roebuck catalogue which constitutes the conventionally “real” world . . . . Is it too much to hope that a system of education may some day be devised, which shall give results, in terms of human development, commensurate with the time, money, energy and devotion expended? In such a system of education it may be that mescalin or some other chemical substance may play a part by making it possible for young people to “taste and see” what they have learned about at second hand . . . in the writings of the religious, or the works of poets, painters and musicians. (Letter to Dr. Humphrey Osmond, April 10th, 1953—in Horowitz & Palmer, 1999, p.30)

In a more literary expression of this notion, Huxley’s final novel Island (1962) portrays an ideal culture that has achieved a balance of scientific and spiritual thinking, and which also incorporates the ritualized use of entheogens for education. The representation of drug use that Huxley portrays in Island contrasts markedly with the more widely-known soma of his earlier novel, Brave New World (1932/1946): whereas soma was a pacifier that muted curiosity and served the interests of the controlling elite, the entheogenic “moksha medicine” of Island offered liminal experiences in young adults that stimulated profound reflection, self-actualization and, I submit, existential intelligence.

Huxley’s writings point to an implicit recognition of the capacity of entheogens to be used as educational “tools”. The concept of tool here refers not merely the physical devices fashioned to aid material production, but, following Vygotsky (1978), more broadly to those means of symbolic and/or cultural mediation between the mind and the world (Cole, 1996; Wertsch, 1991). Of course, deriving educational benefit from a tool requires much more than simply having and wielding it; one must also have an intrinsic respect for the object qua tool, a cultural system in which the tool is valued as such, and guides or teachers who are adept at using the tool to provide helpful direction. As Larsen (1976) remarks in discussing the phenomenon of would-be “shamans” in Western culture experimenting with mind-altering chemicals: “we have no symbolic vocabulary, no grounded mythological tradition to make our experiences comprehensible to us . . . no senior shamans to help ensure that our [shamanic experience of] dismemberment be followed by a rebirth” (p. 81). Given the recent history of these substances in modern Western culture, it is hardly surprising that they have been demonized (Hofmann, 1980). However, cultural practices that have traditionally used entheogens as therapeutic agents consistently incorporate protective safeguards—set, settingviii, established dosages, and mythocultural respect (Zinberg, 1984). The fear that inevitably arises in modern Western culture when addressing the issue of entheogens stems, I submit, not from any properties intrinsic to the substances themselves, but rather from a general misunderstanding of their power and capacity as tools. Just as a sharp knife can be used for good or ill, depending on whether it is in the hands of a skilled surgeon or a reckless youth, so too can entheogens be used or misused.

The use of entheogens such as ayahuasca is exemplary of the long and ongoing tradition in many cultures to employ psychoactives as tools that stimulate foundational types of understanding (Tupper, in press). That such substances are capable of stimulating profoundly transcendent experiences is evident from both the academic literature and anecdotal reports. Accounting fully for their action, however, requires going beyond the usual explanatory schemas: applying Gardner’s (1999a) multiple intelligence theory as a heuristic framework opens new ways of understanding entheogens and their potential benefits. At the same time, entheogens bolster the case for Gardner’s proposed addition of existential intelligence. This article attempts to present these concepts in such a way that the possibility of using entheogens as tools is taken seriously by those with an interest in new and transformative ideas in education.

Bibliography

Abramson, H. A. (Ed.). (1967). The use of LSD in psychotherapy and alcoholism. New York: Bobbs-Merrill Co. Ltd.

Adelaars, A. (2001, 21 April). Court case in Holland against the use of ayahuasca by the Dutch Santo Daime Church. Retrieved January 2, 2002 from http://www.santodaime.org/community/news/2105_holland.htm

Barker, S.A., Monti, J.A. & Christian, S.T. (1981). N,N-Dimethyltryptamine: An endogenous hallucinogen. International Review of Neurobiology. 22, 83-110.

Brown, M.F. (1986). Tsewa’s gift: Magic and meaning in an Amazonian society. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Burroughs, W. S., & Ginsberg, A. (1963). The yage letters. San Francisco, CA: City Lights Books.

Callaway, J.C., McKenna, D.J., Grob, C.S., Brito, G.S., Raymon, L.P., Poland, R.E., Andrade, E.N., & Mash, D.C. (1999). Pharmacokinetics of hoasca alkaloids in healthy humans. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 65, 243-256.

Center for Cognitive Liberty and Ethics. (2003, September 5). 10th Circuit: Church likely to prevail in dispute over hallucinogenic tea. Retrieved February 7, 2004, from http://www.cognitiveliberty.org/dll/udv_10prelim.htm

Cohen, S. (1964). The beyond within: The LSD story. New York: Atheneum.

Cole, M. (1996). Culture in mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cremin, L. A. (1961). The transformation of the school: Progressivism in American education, 1867-1957. New York: Vintage Books.

Czikszentmilhalyi, M. (1996). Creativity. New York: Harper Collins.

Davis, W. (2001, January 23). In Coulter, P. (Producer). The end of the wild [radio program]. Toronto: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

Dobkin de Rios, M. (1973). The influence of psychotropic flora and fauna on Maya religion. Current Anthropology. 15(2), 147-64.

Dobkin de Rios, M. (1984). Hallucinogens: Cross-cultural perspectives. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Dobkin de Rios, M. (1996). On “human pharmacology of hoasca”: A medical anthropology perspective. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 184(2), 95-98.

Dobkin de Rios, M., & Janiger, O. (2003). LSD, Spirituality, and the Creative Process. Park Street Press.

Doblin, R. (1991). Pahnke’s “Good Friday Experiment”: A long-term follow-up and methodological critique. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. 23(1): 1-28.

Egan, K. (2002). Getting it wrong from the beginning: Our progressivist inheritance from Herbert Spencer, John Dewey, and Jean Piaget. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Eliade, M. (1964). Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy. (W.R. Trask, Trans.). New York: Pantheon Books.

Eliade, M. (1978). A history of religious ideas: From the stone age to the Eleusinian mysteries (Vol. 1). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Fikes, J. C. (1996). A brief history of the Native American Church. In H. Smith & R. Snake (Eds.), One nation under god: The triumph of the Native American church (p. 167-73). Santa Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (1999a). Are there additional intelligences? In J. Kane (Ed.), Education, information, transformation: Essays on learning and thinking (p. 111-131). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Gardner, H. (1999b). Intelligence reframed: Multiple intelligences for the 21st century. New York: Basic Books.

Gotz, I.L. (1970). The psychedelic teacher: Drugs, mysticism, and schools. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press.

Greeley, A .M. (1974). Ecstasy: A way of knowing. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Grinspoon, L., & Bakalar, J. B. (1998). Psychedelic drugs reconsidered. New York: The Lindesmith Center (Original work published 1979).

Grob, C. S., McKenna, D. J., Callaway, J. C., Brito, G. C., Neves, E. S., Oberlander, G., Saide, O. L., Labigalini, E., Tacla, C., Miranda, C. T., Strassman, R. J., & Boone, K. B. (1996). Human psychopharmacology of hoasca, a plant hallucinogen used in ritual context in Brazil. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 184(2), 86-94.

Grob, C. S. (1999). The psychology of ayahuasca. In R. Metzner (Ed.), Ayahuasca: Hallucinogens, consciousness, and the spirit of nature (p. 214-249). New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press.

Halifax, J. (1979). Shamanic voices: A survey of visionary narratives. New York: Dutton.

Harman, W. W., McKim, R. H., Mogar, R. E., Fadiman, J., and Stolaroff, M. (1966). Psychedelic agents in creative problem-solving: A pilot study. Psychological Reports. 19: 211-227.

Hofmann, A. (1980). LSD: My problem child. (J. Ott, Trans.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Horowitz, M., & Palmer, C. (Eds.). (1999). Moksha: Aldous Huxley’s classic writings on psychedelics and the visionary experience. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press.

Huxley, A. (1946). Brave new world: A novel. New York: Harper & Row. (Original work published 1932).

Huxley, A. (1962). Island. New York: Harper & Row.

Huxley, A. (1971). The doors of perception & heaven and hell. Middlesex, England: Penguin Books. (Original work published 1954).

Izumi, K. (1970). LSD and architectural design. In B. Aaronson & H. Osmond, (Eds.), Psychedelics: The uses and implications of hallucinogenic drugs (p. 381-397). Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

John-Steiner, V., & Souberman, E. (1978). Afterword. In L. Vygotsky, Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (p. 121-133). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Julien, R.M. (1998). A primer of drug action: A concise, non-technical guide to the actions, uses, and side effects of psychoactive drugs (8th ed.). Portland, OR: W.H. Freeman & Company.

Krippner, S. (1985). Psychedelic drugs and creativity. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 17(4): 235-245.

LaBarre, W. (1989). The peyote cult (5th ed.). Hamden, CT: Shoe String Press.

LaPlante, E. (1993). Seized: Temporal lobe epilepsy as a medical, historical, and artistic phenomenon. New York: Harper-Collins.

Larsen, S. (1976). The shaman’s doorway: Opening the mythic imagination to contemporary consciousness. New York: Harper & Row.

Lewin, L. (1997). Phantastica: A classic survey on the use and abuse of mind-altering plants. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press. (Original work published 1924).

Luna, L.E. (1984). The concept of plants as teachers among four mestizo shamans of Iquitos, northeastern Peru. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 11(2), 135-156.

MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies) Bulletin. (2000). Psychedelics & Creativity. 10(3). Retrieved February 15th, 2004 from: http://www.maps.org/news-letters/v10n3/

Masson, J. M., & McCarthy, S. (1995). When elephants weep: The emotional lives of animals. New York: Delta Books.

Masters, R. E. L., & Houston, J. (1966). The varieties of psychedelic experience. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

McKenna, D.J. (1999). Ayahuasca: An ethnopharmacologic history. In R. Metzner (Ed.), Ayahuasca: Hallucinogens, consciousness, and the spirit of nature (p. 187-213). New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press.

McKenna, D. J., Towers, G. H. N., & Abbot, F. (1984). Monoamine oxidase inhibitors in South American hallucinogenic plants: Tryptamine and -carboline constituents of ayahuasca. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 10(2), 195-223.

McKenna, T. (1992). Food of the gods: The search for the original tree of knowledge. New York: Bantam.

Metzner, R. (1999). Introduction: Amazonian vine of visions. In R. Metzner (Ed.), Ayahuasca: Hallucinogens, consciousness, and the spirit of nature (p. 1-45). New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press.

Myerhoff, B. G. (1974). Peyote hunt: The sacred journey of the Huichol Indians. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Narby, J. (1998). The cosmic serpent: DNA and the origins of knowledge. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam.

Narby, J. (2002). Shamans and scientists. In C.S. Grob (Ed.), Hallucinogens: A reader (p. 159-163). New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam.

Newberg, A., D’Aquili, E., & Rause, V. (2001). Why god won’t go away: Brain science and the biology of belief. New York: Ballantine Books.

Oster, G. (1970). Phosphenes. Scientific American. 222(2), 83-87.

Ott, J. (1994). Ayahuasca analogues: Pangæan entheogens. Kennewick, WA: Natural Products Co.

Pahnke, W. (1970). Drugs and Mysticism. In B. Aaronson & H. Osmond, (Eds.), Psychedelics: The uses and implications of hallucinogenic drugs (p. 145-165). Cambridge, MA: Schenkman.

Pande, C. G. (1984). Foundations of Indian culture: Spiritual vision and symbolic forms in ancient India. New Delhi: Books & Books.

Pert, C. (2001, May 26). The matter of emotions. Paper presented at the Remaining Human Forum, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Reichel-Dolmatoff, G. (1975). The shaman and the jaguar: A study of narcotic drugs among the Indians of Colombia. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Riba, J., Rodriguez-Fornells, A., Urbano, G., Morte, A., Antonijoan, R., Montero, M., Callaway, J.C., & Barbanoj, M.J. (2001). Subjective effects and tolerability of the South American psychoactive beverage Ayahuasca in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology. 154, 85-95.

Riba, J., Rodriguez-Fornells, A., Strassman, R.J., & Barbanoj, M.J. (2001). Psychometric assessment of the Hallucinogen Rating Scale in two different populations of hallucinogen users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 62(3): 215-223.

Ruck, C., Bigwood, J., Staples, B., Ott, J., & Wasson, R. G. (1979). Entheogens. The Journal of Psychedelic Drugs. 11(1-2), 145-146.

Santo Daime. (2004). Santo Daime: The rainforest’s doctrine. Retrieved February 7th, 2004 from http://www.santodaime.org/indexy.htm

Schultes, R. E., & Hofmann, A. (1992). Plants of the gods: Their sacred, healing, and hallucinogenic powers. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.

Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). (1973). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shanon, B. (2002). The antipodes of the mind: Charting the phenomenology of the ayahuasca experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smith, H. (1964). Do drugs have religious import? In D. Solomon (Ed.), LSD: The consciousness expanding drug (p. 155-169). New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Smith, H. (2000). Cleansing the doors of perception: The religious significance of entheogenic plants and chemicals. New York: Tarcher-Putnam.

Smith, H., & Snake, R. (Eds.). (1996). One nation under god: The triumph of the Native American church. Santa Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers.

Spitzer, M., Thimm, M., Hermle, L., Holzmann, P., Kovar, K.A., Heimann, H., et al. (1996). Increased activation of indirect semantic associations under psilocybin. Biological Psychiatry. 39(12): 1055-1057.

Stafford, P. & Golightly, B. (1967). LSD: The problem-solving psychedelic. New York: Award Books.

Stewart, O. C. (1987). Peyote religion: A history. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Strassman, R. J. (2001). DMT: The spirit molecule. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press.

Strassman, R. J., & Qualls, C. R. (1994). Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. I. Neuroendocrine, autonomic and cardiovascular effects. Archives of General Psychiatry. 51(2), 85-97.

Strassman, R.J., Qualls, C.R., Uhlenhuth, E.H., & Kellner, R. (1994). Dose-response study of N,N-dimethyltryptamine in humans. II. Subjective effects and preliminary results of a new rating scale. Archives of General Psychiatry. 51(2): 98-108.

Tupper, K.W. (in press). Entheogens and education: Exploring the potential of psychoactives as educational tools. Journal of Drug Education and Awareness.

União do Vegetal. (2004). União do Vegetal: Centro espírita beneficente. Retrieved February 7th, 2004 from http://www.udv.org.br/english/index.html

United Nations. (1977). Convention on psychotropic substances, 1971. New York: United Nations.

Vonk, J. (2003). Gorilla and orangutan understanding of first- and second-order relations. Animal Cognition. 6(2), 77-86.

Vygotsky, L., (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wasson, R. G. (1968). Soma: The divine mushroom of immortality. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Wasson, R.G. (1980). The wondrous mushroom: Mycolatry in Mesoamerica. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Watts, A. (1969). This is it. Toronto, Ont.: Collier-Macmillan Canada Ltd. (Original work published 1958).

Weil, A. (1986). The natural mind: A new way of looking at drugs and the higher consciousness. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. (Original work published 1972).

Wertsch, J. V. (1991). Voices of the mind: A sociocultural approach to mediated action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Winkelman, M. (2000). Shamanism: The neural ecology of consciousness and healing. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

Zinberg, N. E. (1984). Drug, set, and setting: The basis for controlled intoxicant use. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

i The 1971 United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances allows for indigenous peoples to use traditional medicines and sacraments even if those substances are prohibited under international drug control treaties (United Nations, 1977, Article 32).

ii Santo Daime is the name of the sacrament as well as the religion.

iii Writers and drug aficionados William S. Burroughs and Allan Ginsberg (1963) published an account of their experiences seeking out and drinking ayahuasca in South America in the early 1960s, but their report was mostly negative and did not inspire many others to follow in their footsteps. As ethnobotanist Wade Davis remarks, “ayahuasca is many things, but pleasurable is not one of them” (2001).

iv The original seven types of intelligence Gardner (1983) proposed were: linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, musical, kinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal.

v Eliade (1964) identifies two primary ways of becoming a shaman: 1) hereditary transmission, or falling heir to the vocation in a family legacy passed down from generation to generation; and 2) spontaneous vocation, or being called to shamanism by the spirits. Prodigious existential intelligence may be manifest in either case.

vi Here I conceptually separate education and schooling; unfortunately, I don’t see the latter institution—the legacy of 19th-century homogenizing and democratizing socio-political programs (Cremin, 1961; Egan, 2002)—as inspiring much optimism for an embracing of existential intelligence.

vii Gotz (1970) argues that the practices of teachers might benefit from the mind-expanding potential of psychedelics.

viii “Set is a person’s expectations of what a drug will do to him [sic], considered in the context of his whole personality. Setting is the environment, both physical and social, in which a drug is taken” (Weil, 1972/1986). These factors influence all psychoactive drug experiences, but psychedelics or entheogens especially so.